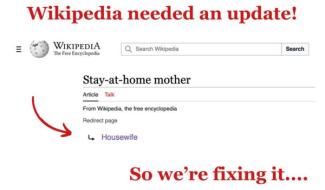

As our 40th Anniversary project, we wrote this new article for Wikipedia on Stay-at-Home Mothers. Representation matters, and the millions of at-home mothers around the world must not be ignored. Care for children has value, whether it's done by paid providers or parents themselves.

Posted to Wikipedia on May 7, 2024.

Stay-at-Home Mother

A “stay-at-home mother” (alternatively, ''stay-at-home mom'' or “SAHM”) is a mother who is the primary caregiver of the children. The male equivalent is the stay-at-home dad. The gender-neutral term is stay-at-home parent. Stay-at-home mom is distinct from a mother taking paid or unpaid parental leave from her job. The stay-at-home mom is forgoing paid employment in order to care for her children by choice or by circumstance. A stay-at-home mother might stay out of the paid workforce for a few months, a few years, or many years.

Many mothers find that their choice to be at home is driven by a complex mix of factors, including their understanding of the science of human development in the context of contemporary society. (1,2,3,4) They are also likely to consider their values, desires and instincts. (5,6) Some mothers are driven by circumstances: a child’s special needs and/or medical condition may require great amounts of time, care and attention;(7) the family may lack affordable, quality childcare;(8) a family residing in a rural area may find it impractical to travel for childcare.(9) Other mothers may prefer and desire to stay at home with their children but must work out of the home to make an income to support the family.(10)

The stay-at-home mother’s role entails physical, emotional and cognitive labor. This work is not exclusive to stay-at-home mothers; mothers who earn income still take on much of this labor as well. Fathers may share some of these responsibilities. While a mother may do the physical work of preparing meals, running errands and grocery shopping, cleaning the home, doing laundry, and providing care to her child or children, she also often anticipates her family’s needs, identifies ways to satisfy them, makes decisions and monitors progress.(11) She plans the daily meals, outings and activities, baths, naps and bedtime. She not only provides physical care through a child’s illness, she consults medical professionals as necessary. She also often takes the lead in managing routine medical and dental appointments, thinking about and planning time together with extended family, and planning for holidays and special occasions. Other tasks may include researching, hiring, and managing outside help including house cleaners, repairmen, or tutors and babysitters.

There is no term that has popularly replaced stay-at-home mom or stay-at-home mother. At-home mothers are diverse; they range across the spectrum of characteristics such as age, economic status, educational and career achievements, political and religious beliefs, and more.(12)

Understanding the Statistics on Mothers and Work

At-home mothers exist throughout the world. However, determining the number of at-home mothers is fraught with pitfalls. Some mothers earn income but don’t report it.(13) And many mothers who consider themselves “at home” are counted as “working mothers” due to the definition of “employed person.”(14)

For example, in the United States, in 2021 the federal Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) showed labor force participation of mothers with children under 18 years of age was 71.2%, leaving 28.8% to be mothers with children under 18 outside of the labor force.(15) These mothers who are outside of the labor force are otherwise known as stay-at-home mothers. They are not considered part of the labor force because they are not employed for pay nor are they unemployed, meaning available and searching for paying work.(16)

The definition of employed person by the BLS is this:

“Employed persons are all those who, during the survey reference

week, (a) did any work at all as paid employees; (b) worked in their own

business, profession, or on their own farm; or (c) worked 15 hours or more as

unpaid workers in an enterprise operated by a member of the family.”(17)

By this definition, a mother could have worked just one hour and would be considered a working parent for statistical purposes, yet that mother may consider herself to be a stay-at-home mother because that is what she did for the vast majority of her time. For decades, the statistics have been widely misused to imply that all “working mothers" are employed full-time and in need of all-day child care and other policies crafted especially for them. This has serious consequences for millions of parents and children as they are left out of public policies.(18,19)

Stay-at-Home Mothers and the Economy

Following the industrial revolution, when men began to work outside of the home,(20) mothers had the job of educating children to be productive members of the labor market.(21) Such was essential “to the development of a vibrant capitalist economy.”(22)

Still, the work of stay-at-home mothers is not included in calculations of the U.S. gross domestic product (GDP),(23) “a monetary measure of the market value of all the final goods and services produced in a specific time period by a country or countries.”(24) When the GDP was first developed in the early 1930s, “its calculations were limited to the total monetary value of goods and services that were sold,” leaving out intangibles like “improvements in surgical techniques, the value of clean water, or the care provided by a family member.”(25) Much of the unpaid work done by stay-at-home mothers was excluded from the measure. As Ann Crittenden points out in her book “The Price of Motherhood,” this results in “absurdities” where for example a nurse bottle feeding a baby is included in the GDP but a mother doing the same thing is not. Another source points out: “The world of work has holistically dominated and been valued over the world of care.”(26)

Worldwide, the unpaid work of caregiving is worth $10.8 trillion a year and done mostly by girls and women.(27) When nations and global aid organizations make economic decisions based only on paid work, they often have unintended negative impacts on unpaid caregivers.(28,29) Perpetuating a false dichotomy between “at home” and “working” results in family policies that exclude millions of families.(30) Scholars and advocates for at-home mothers and for unpaid caregiving call for change in everything from how “work” is defined and measured to how economies are structured.(31,32) For example, in “Care: The Highest Stage of Capitalism,” Premilla Nadasen reveals the inequities of the for-profit care economy. She points to the essential human ethic of caregiving and the elements of joy and community-building that constitute a caring society.(33)

Advocacy for Stay-at-Home Mothers

Global and regional organizations are advocating for the interests of stay-at-home mothers and others who do unpaid domestic labor and care work. Mothers at Home Matter represents mothers and fathers in the UK and internationally, working for an “economic level playing field.”(34) In Europe, 19 organizations campaign together as FEFAF (Fédération Européenne Des Femmes Actives En Famille / European Federation of Parents and Carers at Home). This group has said: "Unpaid care should be equally valued, protected and recognised on a human, social and economic level."(35) In the U.S., Family and Home Network campaigns for inclusive family policies that would benefit all families, equitably supporting all care.(36) The Global Women's Strike and Women of Colour GWS issued an open letter to governments: "We demand a care income across the planet for all those, of every gender, who care for people, the urban and rural environment, and the natural world."(37) More than 100 organizations hailing from Myanmar to the United States, from India to the Netherlands, signed the letter in support.(38) Reports on government programs, as well as analyses of policy proposals, illuminate the need to recognize and support at-home parents and caregivers.(39,40,41) The imperative to recognize and provide economic support for at-home mothers and other caregivers is worldwide.

______________

Footnotes:

1 Schore, A.N. & Narvaez, D. (2014). Neurobiology and the Development of Human Morality. Norton Professional Books. https://wwnorton.com/books/Neurobiology-and-the-Development-of-Human-Morality/

2 Center on the Developing Child at Harvard University. Science: Key Concepts. Accessed April 8, 2024. https://developingchild.harvard.edu/science/key-concepts/

3 Garner, A. & Yogman, M., Committee on Psychosocial Aspects of Child and Family Health, Section on Developmental and Behavioural Pediatrics, Council on Early Childhood. (2021). Preventing Childhood Toxic Stress: Partnering With Families and Communities to Promote Relational Health. Pediatrics August 2021; 148 (2):e2021052582. https://publications.aap.org/pediatrics/article/148/2/e2021052582/179805/Preventing-Childhood-Toxic-Stress-Partnering-With

4 Center for the Study of Social Policy: Nurture Connection. Why Early Relational Health Matters. Accessed February 7, 2024. https://nurtureconnection.org/family-partnership/

5 De Marneffe, D. (2019). Maternal Desire: On Children, Love, and the Inner Life. Scribner. https://www.simonandschuster.com/books/Maternal-Desire/Daphne-de-Marneffe/978150119827

6 Kindred World. Accessed March 23, 2024. https://kindredworld.org/

7 Weaver MS, Neumann ML, Lord B, Wiener L, Lee J, Hinds PS. Honoring the Good Parent Intentions of Courageous Parents: A Thematic Summary from a US-Based National Survey. Children. 2020; 7(12):265. Accessed April 9, 2024. https://doi.org/10.3390/children7120265

8 Gould, E. & Blair, H. (2020). Who's Paying Now? The explicit and implicit costs of the current early care and education system. Washington, DC, Economic Policy Institute. https://www.epi.org/publication/whos-paying-now-costs-of-the-current-ece-system/ Accessed Apri 9, 2024

9 Colyer, J. and National Advisory Committee on Rural Health and Human Services. (2023). Childcare Need and Availability in Rural Areas. Accessed April 9, 2024 https://www.hrsa.gov/sites/default/files/hrsa/advisory-committees/rural/nac-rural-child-care-brief-23.pdf

10 What to Expect Community Forum. November 27, 2021. “How can I be a SAHM? I Can’t Afford It…” EverydayHealth. Accessed March 18, 2024.. (https://community.whattoexpect.com/forums/april-2022-babies/topic/how-can-i-be-a-sahm-i-cant-afford-it-125196966.html

11 Daminger, Allison, “The Cognitive Dimension of Household Labor,” American Sociological Review, 2019, vol. 84(4)609-633.

12 Hakim, C. Key Issues in Women’s Work: Female Diversity and the Polarisation of Women’s Employment. (2004). Routledge-Cavendish. https://www.routledge.com/Key-Issues-in-Womens-Work-Female-Diversity-and-the-Polarisation-of-Womens-Employment/Hakim/p/book/9781904385165

13 Davis, L.S.. (2024). Housewife: Why Women Still Do It All And What To Do Instead. Legacy Lit Hachette Book Group, page XVIII.

14 Burton, L., Dittmer, J. & Loveless, C. (1992, 1996). What’s a Smart Woman Like You Doing at Home? Chapter 6: Setting the Record Straight. Mothers at Home. Accessed January 15, 2024. https://familyandhome.org/statistics-mothers-and-work-setting-record-straight

15 U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2022). The Economics Daily, Labor force participation of mothers and fathers little changed in 2021, remains lower than in 2019, Accessed April 10, 2024. https://www.bls.gov/opub/ted/2022/labor-force-participation-of-mothers-and-fathers-little-changed-in-2021-remains-lower-than-in-2019.htm

16 U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2022). Economic News Release: Employment Characteristics of Families. Accessed March 5, 2024 https://www.bls.gov/news.release/archives/famee_04202022.htm

17 U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2022). Economic News Release: Employment Characteristics of Families. Accessed March 5, 2024. https://www.bls.gov/news.release/archives/famee_04202022.htm

18 Ted. (December 2021) How Moms Shape The World / Anna Malaika Tubbs. YouTube. Accessed April 25, 2024. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eSwg04B81YM

19 Burton, L., Dittmer, J. & Loveless, C. (1992, 1996). What’s a Smart Woman Like You Doing at Home? Chapter 6: Setting the Record Straight. Mothers at Home. Accessed January 15, 2024. https://familyandhome.org/statistics-mothers-and-work-setting-record-straight

20 “The Role of Women in the Industrial Revolution” from The World of Barilla Taylor: One Mill Girl’s Experience in Lowell, Tsongas Industrial History Center, https://www.uml.edu/tsongas/barilla-taylor/

21 Crittendan, A. (2010). The Price of Motherhood: Why the Most Important Job in the World is Still the Least Valued. Picador. 10th Anniversary Edition: page 51.

22 Crritendan, A. page 49.

23 U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Household Production. Accessed March 5, 2024. https://www.bea.gov/data/special-topics/household-production

24 Wikipedia. Gross Domestic Product.Accessed March 12, 2024 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gross_domestic_product

25 Crittenden, A. Page 65-66.

26 Reid Boyd, E. and Letherby, G. eds. (2014) Stay-at-Home Mothers: Dialogues and Debates. Demeter Press, page 3.

27 Oxfam. Not all gaps are created equal: the true value of care work. Access March 13, 2024 https://www.oxfam.org/en/not-all-gaps-are-created-equal-true-value-care-work

28 Himmelweit, S. (2002) Making Visible the Hidden Economy: The Case for Gender-Impact Analysis of Economic Policy. Feminist Economics, vol. 8, issue 1. Accessed March 13, 2024 https://econpapers.repec.org/article/taffemeco/v_3a8_3ay_3a2002_3ai_3a1_3ap_3a49-70.htm

29 Nerine Butt, M., Kamal Shah, S. & Ali Yahya, F. Caregivers at the frontline of addressing the climate crisis. Gender & Development. Volume 28, 2020. Accessed March 14, 2024. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/13552074.2020.1833482

30 Family and Home Network. Campaign for Inclusive Family Policy. Feb 12, 2024. Accessed March 13, 2024. https://www.familyandhome.org/articles/campaign-inclusive-family-policies

31 Revaluing Care in the Global Economy: Global Perspectives on Metrics, Governance, and Social Practices. Accessed April 12, 2024. https://www.revaluingcare.org/

32 Center for Partnership Systems. https://centerforpartnership.org/ Accessed April 12, 2024.

33 Nadasen, P. (2023) Care: The Highest Stage of Capitalism. Haymarket Books.

34 Mothers at Home Matter. https://www.mothersathomematter.com

35 Fédération Européenne Des Femmes Actives En Famille. Accessed March 12, 2024 https://www.fefaf.be/about-us.html

36 Family and Home Network. Campaign for Inclusive Family Policy. Feb 12, 2024. Accessed March 13, 2024. https://www.familyandhome.org/articles/campaign-inclusive-family-policies

37 Global Women’s Strike. Open letter to governments – a Care Income Now! March 27, 2020. Accessed March 12, 2024. https://globalwomenstrike.net/open-letter-to-governments-a-care-income-now/

38 Global Women’s Strike. Endorsers to the Open Letter to Governments – A Care Income Now! January 23, 2021. Accessed March 12, 2024. https://globalwomenstrike.net/organizational-endorsers-to-the-open-letter-to-governments-a-care-income-now/

39 Minoff, E. & Cocci, A. Strategies to Compensate Unpaid Caregivers: A Policy Scan. Center for the Study of Social Policy. March 2024. Accessed March 2024. https://cssp.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/Strategies-to-Compensate-Unpaid-Caregivers-A-Policy-Scan.pdf

40 The Center for Social Justice. Parents Know Best: Giving Families a Choice in Childcare. October 2022. Accessed March 2024. https://www.centreforsocialjustice.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/Parents_Know_Best-CSJ.pdf

41 Van Leer Foundation. Early Childhood Matters 2023. January 30, 2023. Accessed March 2024. https://vanleerfoundation.org/publications-reports/early-childhood-matters-2023/?mc_cid=1499d2a7fe&mc_eid=7888fd5cb6