by Catherine H. Myers

Scholars have tried to define parenting, to measure various attempts to train or teach parenting, to observe and define various styles of parenting and to try to analyze how parenting affects children. Marc Bornstein, Head of Child and Family Research at the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, has edited an extensive collection of scholarly work on parenting; the 2nd edition of the Handbook of Parenting consists of five volumes.1 In an essay for the proceedings of the national Parenthood in America conference, Dr. Bornstein writes:

“Despite the fact that most people become parents, and everyone who ever lived has had parents, parenting remains a somewhat mystifying subject about which almost everyone has opinions, but about which few people agree. One thing is certain: It is the principal and continuing task of parents in each generation to prepare children of the next generation for the physical, economic, and psychosocial situations in which those children must survive and thrive.”2

How do parents prepare children for a future that no one can forsee?

In their book The First Idea: How Symbols, Language, and Intelligence Evolved from our Primate Ancestors to Modern Humans, Stanley I. Greenspan, M.D. and Stuart G. Shanker, D.Phil. emphasize that human evolution continues today, and that parent-infant relationships are at the center of human development and survival. They trace the development of intellectual growth and reflective thinking through human evolution and history. Examining the state of humanity across the globe, they note: “in an interdependent world, the unit of survival is no longer the individual or even the small group, but the global group.” And they note that in order for constructive patterns of interdependency to develop (rather than the alternative, destructive patterns), there is a need for a “true morality of interdependence.” The book is a powerful statement of the critical importance of intimate, two-way relationships in human development. These intimate relationships are the base on which a child builds relationships with others in the community, the nation, the world. The future of humanity depends on relationship-building.3

Unfortunately, in the U.S. today, parenting is seen as a private enterprise, a personal choice—as though human civilizations would continue whether or not anyone ever again chose to raise a child well. There are widespread assumptions that parents are obligated to simply “do a good job” without asking for, or expecting, assistance from others. Far too many parents face difficult circumstances: they are too isolated, don’t spend enough time with their infant, don’t have others helping to care for the infant, and have inadequate economic resources.

Meanwhile, scientific research accumulates exponentially, demonstrating the critical importance of nurturing. In recent years researchers have come up with creative, scientific studies that measure some of the effects of parenting behaviors. Intimate nurturing relationships are highly complex, and they include elements of love, cherishment and intuitive two-way communication.

And who nurtures the parents?

As developmental psychologist and parent educator Harriet Heath says, our very language has limitations that make it difficult to talk about what it is that parents do: "The English language does not have words that combine an emotional feeling component with a cognitive thoughtful one. We end up talking about either or yet in parenting the two go together…. The parent guides in a loving caring manner adapting what she does to who the child is."4 In her writings for parents, Harriet Heath examines parental roles, expectations, and the importance of considering our values. She also reminds us: “Parents have needs, too. Our culture often forgets that…and babies don’t consider it. But parents need food and shelter; they need to be loved; they are curious and need to feel competent.”5

The perspective most often taken by scientists is to look at the effects of parenting (what does parenting do to the child?). Although that is by far the most commonly used perspective in studying parenting and parents, there is another perspective: the parental experience of raising a child.

In 2003 Alice van der Pas of the Netherlands introduced new theoretical ideas about parenting in her book, A Serious Case of Neglect: The Parental Experience of Child Rearing. With empathy and understanding, van der Pas describes parenting as: “like the unending rehearsal, under ever-changing circumstances, of a particularly complex task.”6

Van der Pas offers a thorough rethinking of many myths about child rearing. Rather than categorizing children as either "at risk" or not, she asks us to recognize that children are put at risk when there are not adequate buffering processes [she uses the term moderating factors]. The first moderating factor is "a community which acknowledges the importance of parenting" and by "acknowledge" she means not only respect and encouragement but also concrete support, including economic support and also the nurturing of parents. As van der Pas emphasizes and strong research demonstrates, appropriate moderating factors such as interventions, support and services can improve a parent's well-being and nurturing behaviors.

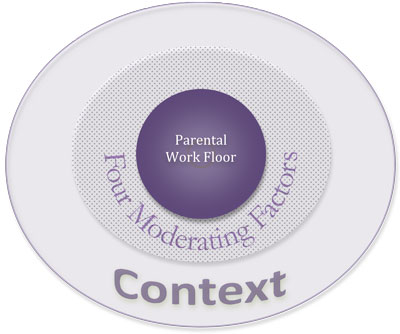

The following models offer a visual guide and brief summary of the Van der Pas theory of the parental experience of child rearing.

The first model shows the big picture, with the parental work floor in the center, set in the context of everything in the parent's world and influenced by moderating factors:

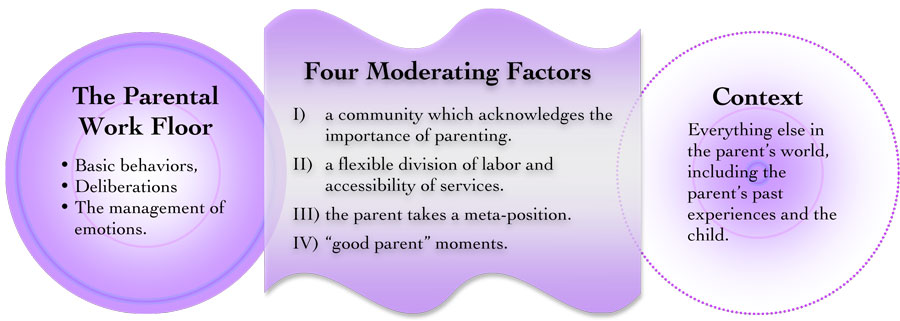

Next, the model is expanded to allow room for some explanatory notes:

Let’s take a look at the three parts of the van der Pas model:

Parental Work Floor – behaviors (what parents do), deliberations (when and how much to do) and the management of emotions. Van der Pas describes five parenting behaviors:

- providing safety

- nurturing (van der Pas’ meaning here is limited to providing for a child’s physical health and comfort)

- gauging the child (explained by van der Pas as “the willingness to raise the question” of “who is this child, and what does he need and want?”)

- making demands

- setting limits.

Alice van der Pas emphasizes that each parent’s work floor must be considered individually, giving as an example a mother who reports that her child “makes an awful mess at dinner.” Van der Pas says, “I immediately get a picture of the situation. But this is only my picture. I am aware of the fact that the mother’s reality can be vastly different. What does ‘make an awful mess’ mean there, in her situation, at that particular table? Does [the child] throw food around? Are his clothes covered with soup? …Does he mix potatoes with peanut butter? Does he eat with his fingers? Can he perhaps not control his tongue?”

“Parenting is, and always has been, practiced in a wide range of styles, methods and modes, from strictly traditional to wildly experimental,” says van der Pas. Of course parenting practices vary from one culture to another, and within a culture there are many sub-groups.

Time impacts the Parental Work Floor: as a child grows his/her needs change, and as a parent gains experience and knowledge, some things become easier—but other challenges come along. “Experienced parents can feel as much at a loss when a daughter has her first date, or develops marital problems, as on the day she was born,” says van der Pas.

Next we’ll look at the context...

Context - includes “everything else in the parent’s world, including the parent’s past experiences and the child.” This includes: experiences from your own childhood (and the emotional interactions among family members), your education, work and travel experiences, the other parent and your relationship, your own parents, extended family and friends. Context includes your health, your housing conditions and neighborhood, availability of transportation, and your financial situation. And it includes the characteristics of your child (health, temperament, gender). For each parent, contextual factors vary with time, as the parent grows and changes, as possibly more children are born or adopted into the family, and as the parent is exposed to “current theories about parenting.”

Between the parental work floor and context are Four Moderating Factors:

I. A community which acknowledges the importance of parenting

II. A flexible division of labor and accessibility of services

III. The parent takes a meta-position

IV. “Good parent” moments

Van der Pas notes about contextual factors including parents' relationship difficulties and poverty: "the 'risks' are risky only in so far as we do not 'buffer' them [with moderating factors]".

As Alice van der Pas says, in order for parents to nurture their children, they must themselves be nurtured; and she quotes anthropologist Sarah Hrdy: “Nurturing has to be teased out, reinforced, maintained. Nurturing itself needs to be nurtured.”7 In the Western world and among behavioral scientists, however, van der Pas observes widespread belief that parents themselves do not need to be nurtured. Also, many people think that a not-so-nurturing parent is a fixed contextual factor (or risk factor)--when in reality, and as shown by evidence-based research studies, appropriate and sufficient moderating factors (support, services, interventions) are likely to improve this parent's nurturing behaviors.

The van der Pas theory of the parental experience of child rearing gives us a new framework in which to think about our experiences as parents.

References

1. Marc H. Bornstein, Editor. Handbook of Parenting. 2nd ed. Mahwah, N.J: Erlbaum, 2002.

2. Marc H. Bornstein, “Refocusing on Parenting.” Parenthood in America Edited by Jack C. Westman, M.D., n.d.

3. Stanley I. Greenspan, M.D. and Stuart G. Shanker, D.Phil. The First Idea: How Symbols, Language, and Intelligence Evolved from Our Primate Ancestors to Modern Humans. 1st Da Capo Press ed. Cambridge, MA: Da Capo Press, 2004.

4. Harriet Heath. “Personal correspondence via email to Catherine H. Myers," October 18, 2011.

5. Harriet Heath. Plan How to Get Where You Want to Go in Nurturing Your Children. E-book. Seattle, WA: Parenting Press, 2010.

6. Alice van der Pas. A Serious Case of Neglect: The Parental Experience of Child Rearing: Outline for a Psychological Theory of Parenting. 1st ed. Eburon Publishers, Delft, 2003.

7. Sarah Hrdy. Mother Nature: Maternal Instincts and How They Shape the Human Species. 1st ed. Ballantine Books, 2000.

Originally published in May 2013.